Philip Eil is a journalist from Providence, Rhode Island. He has written several articles, many for acclaimed publications such as The Boston Globe and The Atlantic.

In the late 2000s, Eil learned of a fascinating story he wanted to pursue about a doctor who had overprescribed millions of opioids to Appalachians in southern Ohio. The story consisted of finding out: “What the hell happened to Paul Volkman?”

In the late 2000s, Eil learned of a fascinating story he wanted to pursue about a doctor who had overprescribed millions of opioids to Appalachians in southern Ohio. The story consisted of finding out: “What the hell happened to Paul Volkman?”

Volkman, as it turned out, had obtained his Ph. D. and M.D. from the same institution as Eil’s father, Dr. Charles Eil, who became an endocrinologist while Volkman became a pediatrician with a pharmacology degree. Upon learning of his father’s connection to the doctor who was facing criminal charges for overprescribing and killing his patients, Eil had to know more about the doctor who was facing 12 counts of unlawful distribution of a controlled substance.

Eil’s commitment to telling the story of Paul Volkman’s victims and the doctor himself, took Eil to the town of Portsmouth, Ohio, from 2009 to 2022. Volkman had begun his pain management career in a clinic owned by a woman without a medical license of any kind and with three malpractice lawsuits under his belt. Volkman’s southern Ohio stint lasted from 2003 to 2006.

Despite the utter lack of legitimacy surrounding Volkman, Denise Huffman, the clinic’s owner, and Denise’s daughter Alice, who helped run the clinic, all three went on to thrive in two Portsmouth clinics. On Gay Street, Tri-State Health Care and Pain Management overprescribed hundreds of patients from their on-site dispensary for a cash exchange of around $150 per visit. When that clinic was raided by the DEA, they moved to Findlay Street, just a few blocks down from their first clinic. Upon that clinic being raided as well, Volkman parted ways with the Huffmans and began prescribing straight out of his Portsmouth residence on Center Street until he was raided by police. Quickly, he opened up a clinic in Chillicothe.

At every location where Volkman worked during his southern Ohio years, he tended to prescribe a similar dosage to each patient. When he was at Tri-State, Volkman was the largest purchaser of hydrocodone in the United States.

In 2007, Volkman was arrested in Chicago, where he went home to his family on the weekends during his years as a doctor in Ohio (flying into Columbus and then driving two hours to Portsmouth). Although the distance may have deterred other doctors, Volkman was used to traveling long distances during his years as a locum tenens (temporary placement) doctor who traveled to different states and worked in hospitals in need of doctors due to different circumstances. After Volkman parted with the Huffmans in 2005, his patients were traveling their own distance to Columbus to get their prescriptions filled by a pharmacist who turned a blind eye to the extraordinary amounts of opioids that Volkman prescribed.

Volkman is now serving four consecutive life sentences in prison despite his claims of only wanting to help an underserved area manage their pain. His excuses for the several deaths that he was charged with (12 counts with him being found guilty of directly causing four of those), was that it was the patients’ fault for misusing the drugs, taking other drugs without notifying him or due to underlying health issues. It begs the question, though, that after all of these deaths that happened, sometimes within days of visiting Volkman, how did he not notice a pattern or see that his patients were addicted?

Paul Volkman’s full story is researched and laid out in Philip Eil’s book, Prescription for Pain: How a Once-Promising Doctor Became the “Pill Mill Killer.” Eil’s correspondence with Volkman and visits to midwestern Appalachia span over a decade. In the beginning, Eil never imagined the story that he described as a life calling would have lasted for so long. In the beginning, from 2009 to 2011, Eil wrote down his early notes, most of which never made it into the final book. However, when he received a book deal in 2021, it was time for him to finish fact-checking and begin to solidify the story he had been working on since 2009.

Upon his first arrival in Portsmouth in 2010, Eil met with Andrew Feight, a history professor at Shawnee State University who had just begun his deep dive into the area’s history. To better understand why Portsmouth became an epicenter of the opioid epidemic in the United States, one must first look at Portsmouth’s history.

In the 1830s, the river town of Portsmouth saw the revolution of transportation with steamboats, canal systems and the development of iron and steel industries. The 1850s brought railroads which helped spur the development of the shoe industry. Portsmouth was a booming, industrial town by the Ohio River by the 1890s. The population began to leave, though, with the 1937 flood that devastated the city. From there, Portsmouth began losing its shoe factories. In the 1970s, one of Portsmouth’s biggest employers, the steel mill in New Boston, began to close. With the deindustrialization of the Rust Belt and the continuing decline of available jobs, Portsmouth residents left. By the end of the 20th century, social issues, poverty and structural unemployment became the norm for the city and its remaining residents.

“In some ways,” said Feight, “it left the city primed for the opioid epidemic.”

Eil agreed, stating that Portsmouth’s financial struggles led to an easy get-rich-quick scheme where everyone made money in the drug business. The doctors made money from prescribing excessive amounts of opioids, and the patients thrived when selling them. Prescription for Pain includes interviews with several of Volkman’s victims’ loved ones, who expressed how they once believed selling pills was the only easy way to make money. All they had to do was visit Volkman’s office to get a prescription.

As Eil began his research journey, he talked to “anybody and everybody” who would speak to him about Portsmouth in order to better understand the community. He noted that not every interview he conducted made it into the book.

“In some cases,” Eil said, “[I] was walking up to people on the street; talking to bartenders; talking to people at the health department.”

In journalistic terms, Eil was susceptible to being labeled a parachute journalist. These types of journalists are the ones who are brought in to report on a story in a town they are not familiar with. This unfamiliarity tends to lead to inaccurate reporting of the story and the journalist being seen as untrustworthy. Although Eil still expressed concerns over this label, he shared that in the lengthy research process of Portsmouth and the story, he felt as though he had passed that “drive-by journalist” stage.

All of this dedication and research, though, was needed to convey not only Volkman’s story but his patients’ and Portsmouth’s as well. When looking at a person and their crimes, the surroundings of that person must also be determined and understood.

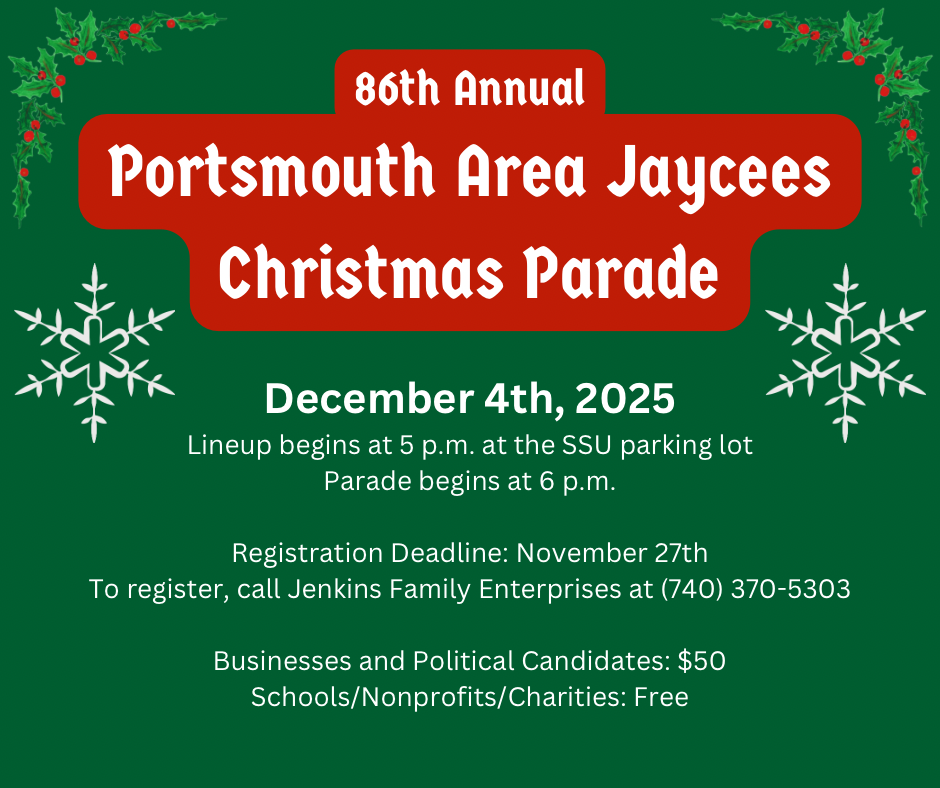

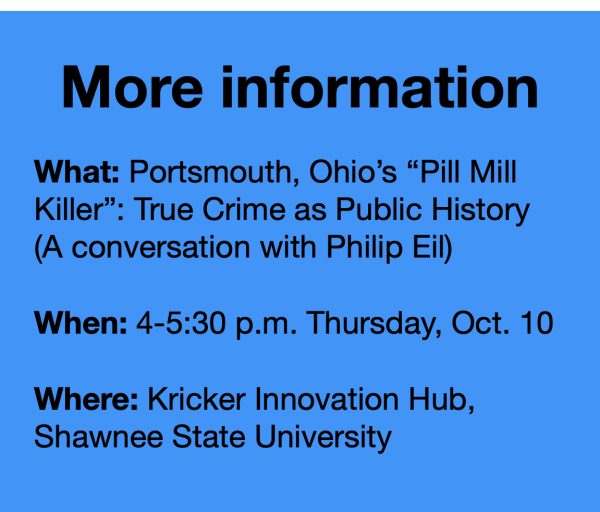

On Thursday, Oct. 10, Eil will be discussing his book with Feight, as well as the correlation between true crime and public history. The event will take place in the Kricker Innovation Hub from 4 to 5:30 p.m.

Public history is often defined as the opposite of academic history. Instead of a group of scholars writing for other scholars, public history is public-facing, meaning it’s history for the general public as the intended audience.

During Eil’s second book tour, he will be visiting places in the tristate area until Oct. 16. Compared to his first book tour in states like Rhode Island and Massachusetts, Eil recounted prior to the start of the tour how he figured the two would be different.

“In Rhode Island, a lot of people know me but don’t know the story,” Eil said. “Here [in Portsmouth], it’s kind of flipped. People know the broad story of opiates, and pain clinics and overdoses. But they may not know me. In my talks in Rhode Island, I have to explain [and] introduce people to this place…A majority have never heard of Portsmouth, Ohio. I don’t need to do that here.”

Eil continued with his concerns about the sensitivity of the topic no matter where he went. In Portsmouth, though, he feels more cautious, but eager to speak with people. The town of Portsmouth tends to have a closer, vested interest in the subject due to its history. Still, Eil expressed his excitement be in town and have more conversations with anyone who wanted to talk with him.

“It’s thrilling to be back,” Eil said.